| Back | Index | Next |

Translator: Eduardo Freire Canosa

(University of Toronto Alumnus)

I grant the translations herein to the public domain

(Cántiga, 1869)

Translator's Notes

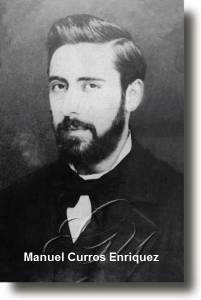

"Unha Noite na Eira do Trigo" was the first poem that young Enríquez penned in the Galician language.

"Unha Noite na Eira do Trigo" uses one affectionate diminutive, "olliños" (2.4): Dim. and pl. of "ollo" (eye) translated "dear eyes." Other options: cherished eyes, longed-for eyes, lovely eyes.

Explanation of some words, terms or expressions

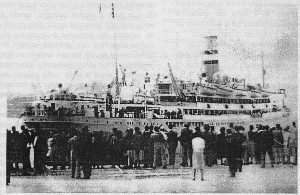

Of a rogue steamboat slaver (4.2). By the early 1830's the Spanish colonial authorities of Cuba, the landowners and the sugar exporters realized that the growing population of African slaves posed a serious threat to the stability of the Caribbean island. In 1853 slave trafficker Urbano Feijóo Sotomayor and captain general Valentín Cañedo elaborated a White Paper to fill the demand for slave labour in the sugar cane plantations with Galician workers brought in under a five-year contract. The plan was approved by the Spanish Courts on May 2, 1854. In March of that same year the frigate Villa Neda transported the first 314 Galician workers to Havana. The official plan promised a decent life in Cuba. However the reality turned out to be very different...Upon arrival the employer secluded the workers in barracks lacking the minimum living conditions and hygiene; this was to be their residence during a period of "adaptation." The barracks were in fact derelict venues where landowners flocked to buy workers: a marketplace for buying and selling human "cargo." The food provided was sparse and dismal, potatoes and salt-cured meat, and the period of "adaptation" lasted for as long as it took to negotiate the price of a worker with Feijóo. Ramón Fernández Armada the director of the Havana enterprise describes the working conditions thus,

The Galicians were taken from their homes tricked with false and vague promises and have arrived in Cuba to find opprobrium, fraud, ignominy and death. Until now approximately 500 have died from hunger, ill treatment or as a result of being abandoned [...] Their entire blame consisted in asking for bread to avert starvation; and to restrain the [rebellious] impulse the bosses ordered that they should be held in foul-smelling quarters, chained and fettered, naked and barefoot. They feed them rotting meats which the African blacks reject. They force them to work fifteen hours daily by way of the whip, the stick and the sword. This situation has led them to despair and the ones who did not escape died in the byways, the jails or the hospitals. A scandal—horrendous—a slaughter.1

Musical Adaptation

"Unha Noite na Eira do Trigo" was put to music by Juan Montes Capón and subsequently by José Castro González alias Chané. The song became an instant hit. Over the years the common people altered the original text slightly to yield, for example, the modern lyrics below. The television program "No bico un cantar" of Radio Televisión de Galicia aired on March 5, 2013, gave an in-depth study of this ballad.

|

|

Joaquín Deus (vintage recording) |

|

|

Cantigas Da Terra (vintage recording) |

|

|

Soundtrack from the 1959 movie La Casa de la Troya |

|

|

Pucho Boedo from the 1974 album Miña Galicia Verde |

|

|

Ana Kiro from the 1979 single Ana Kiro |

|

|

Rosa Cedrón and Cristina Pato from the 2010 album Soas |

|

|

Ana Häsler (to min. 4:30) and the Galicia Philharmonic at the Amadeo Roldán Theatre in Havana (Cuba) |

|

|

Uxía, Christina Margotto, Jed Barahal and Sérgio Tannus |

|

|

Egeria String Quartet |

For those who saw a ship leave port...

|

Unha noite na eira do trigo,

I a coitada entre queixas decía:

Os seus ecos de malencolía

Lonxe dela, de pé sobre a popa

I ó mirar as xentís anduriñas

Mais as aves i o buque fuxían

Noites craras de aromas e lúa,

Dun amor celestial, verdadeiro, |

Once upon a night in the wheat fields

And the poor girl said between plaints,

Her echoes of melancholy

Far away from her, standing at the stern

And upon watching the gentle swallows

But the birds and the vessel sped onward

Clear nights of fragrances and moonlight,

Away from a heavenly, genuine love |

| Back | Index | Next |